The Silent Comedy are on a roll. Thanks to their high-energy performances and whiskey-soaked songwriting, the San Diego band has amassed a passionate following, repeatedly selling out the Casbah as if it were their grandma’s basement. The stylish six-piece will return to the venue on April 2nd to celebrate the release of their sophomore album, Common Faults. We sat down with verbose singer/keyboardist Jeremiah Zimmerman to discuss the album, the problems with consumerism, and the band’s love of mustaches.

Owl and Bear: You recorded part of the album at Blue Roof Studios, and part of it at your own practice space. Was this solely a financial decision, or is there something about the sound you get from your own space that makes you want to record there?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: It started as financial and time. But then as we started going on, we found that we got a lot of really cool sounds at our space that I don’t think we would have gotten otherwise. So we started taking advantage of that: not seeing it as a limitation but as a signature feel. So much so that we actually even had Sean [Cornell, the album’s engineer] comment on some of the guitar tones that we got, asking what we did to get it, which I thought was kind of cool, because he has all the greatest equipment in the world, and he’s like “What did you do to get that guitar to sound that way?” And I’m running it down for him and he’s making a note to buy that mic.

Owl and Bear: You and your brother Josh handle the majority of the songwriting in the band. Do the two of you collaborate on a song, or do you each bring your own independently written songs to the table? At what point does the rest of the band contribute?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: The normal process is that I tend to bring more completed songs than Josh does. Usually he brings me a melody with lyrics that he’ll sing out, or he’ll have a specific thing that he’s come up with on guitar or bass.

A good example is “Moonshine.” The main guitar part of the song was all him with his guitar. He did that one thing, and then said “I’ve got this idea for a song,” and sang the first verse for me. I took that and wrote two other parts for it and structured it all out, and arranged how it should go. Then, he finished off writing the words and ran them back by me, and I had a couple of ideas for changes, so we collaborated.

And then typically, we bring it into the band and say, “Hey we’ve got this song that Josh wrote,” and everybody jumps on it and starts throwing ideas at it. That was our writing style for the first three years or so, but I think this record has been a lot more collaborative. I’ll come in with a segment, and someone else will suggest an idea. That happened on a couple of these songs, but I tend to bring in the complete songs and Josh tends to bring in sort of half-songs, and I finish them.

There are a couple songs on this record, like “Poison,” that were a direct collaboration where he was just playing this bass line, I added some stuff to it, he sang something, and I sang something, and we just batted it back and forth, writing the song simultaneously. That rarely happens, though; usually one of us has the germ of it, and it expands from there.

But the new stuff we’ve been writing — that’s not on this record — has been more collaborative, especially with Chad [Lee], who’s drumming with us now. He has a ton of ideas, and he’s really interested in getting in-depth and trying to piece out every bit of the song, which we’ve never had before.

Owl and Bear: That’s unusual for a drummer.

Jeremiah Zimmerman: Yeah, very much so. He wants to play the song five or six times just to hear what the violin’s doing. Usually you have to get the drummer’s attention, so the fact that he’s instigating that is really cool. So yeah, I think we’re heading toward a more collaborative process, but I do tend to be a control freak, so I’m trying to let go of the reins.

It helps that everyone in the band is a better musician now than when we started. When we first started, every single show, every single song, someone would ask me what the chords were for that song. Every single time. After every song, I would hear someone whisper, “What are the chords for this thing?” So we had to write songs that were loops that didn’t really change a whole lot — like four chords in a row, and the only changes would be loud or soft, or the melody, because nobody could remember anything. We didn’t practice enough.

But now we can write more linear stuff with a lot of chord changes or slight variations that would have been confusing four or five years ago. Now, we’re like “Oh yeah, we can do that.” It’s nice.

Owl and Bear: A lot of the songs on this album were previously included on your first album, Sunset Stables, and your self-titled EP. What made you want to re-record them?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: We did the first full-length record with one mic, an Mbox, and a laptop in our previous practice space, which was a death trap. It leaked when it rained, there was mold growing everywhere, and we had no ability to mic the drums at all. We did everything in that space, and we only had drums on, like, three songs. We did almost everything acoustically and it was an odd record. It was only supposed to be a few songs, but then it expanded into like ten or eleven. We just kept recording these little guitar and voice songs until we had too many, and we ended up putting it out as a full-length.

But we always felt that that record wasn’t how we wanted it to be. Songs like “Moonshine” or “All Saints Day” were so haphazard and thrown together in a way that felt like we didn’t do them justice. Now that we’ve been playing them awhile, we’ve expanded on what they are and made them this whole other thing.

So we took some songs off that record, some songs off the EP, and we re-examined, re-recorded, and added them to a handful of songs we recently wrote and said “let’s move on.” Some stuff showed its age, and I thought, “Wow, that was a very simple time of songwriting for us, and we’ve grown out of it.” There’s an obvious shift.

But we also sensed a glimmer of what we could write in the future, and that’s what we included on this record. A song like “Moonshine,” which was an old, old song, and the first time we were like, “We can get edgier, we can get harder with this.” There was a bit of nostalgia. Then, there are songs like “Exploitation,” which we never could’ve written back then. “Moonshine” started us down that road, so to include that on the record is a way of saying, “This is how it started, this is where it ended.”

And “All Saints Day” was one that had huge dynamic changes, starting with just a guitar and a voice ending with a horn and string section. Last time we recorded that, we were recording without any direction at all. That song was written days before we finished recording Sunset Stables, and we just threw it in there. Now, after playing it for a couple of years, we were ready to give it a fair shake. So we went back in and reexamined it.

We also wanted to reexamine “All Saints Day” again because it really influenced our sound and how we write now. Another reason was that we really wanted to try and capture the energy of our live show on the new record. It’ll never sound the same, which is probably a good thing, but we wanted an energy level that reflected the live show, so that was a factor, too.

Owl and Bear: The album is about people’s flaws. Since the songs were sometimes written years apart from each other, when did you decide on that concept?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: When we put together the track list, we actually tracked thirteen songs for a ten-song record, with one intro track. When we looked at all thirteen songs, we were like, “Why did we pick these songs? Why do they seem to work together? What is the commonality?” We were pretty honest about it. Were these just the songs we liked the most, or was there a thread going all the way through them?

Every time we looked at it, every song had some sort of error in it — either in ourselves or what we see around us in society. And that can get really tedious when you start talking about albums, especially now in the post-album world with iTunes and all that. But we didn’t want it to be a bunch of songs we threw together. We felt like the EP was like that, a little disjointed and moving in too many directions at once. We wanted something that was a little more cohesive.

Owl and Bear: What types of faults do you address?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: In every song, there’s jealousy or excess. There’s a whole song about drinking too much, one about child trafficking, songs about religious hypocrisy, deceit, and all the things that are wrong with the world. Every time we talked about the record, we were like, “It’s kind of dark,” but we didn’t really want to evoke skulls and Hot Topic, so we said “It’s not ‘dark’ so much as it is just ‘flawed’ and riddled with faults.”

They were the faults you see everywhere, so much so that you can get jaded. The only way you can really see it is when it’s exemplified in an extreme way. Like, we all want to consume with a disregard for other people, but you don’t realize that until you punch someone to take their wallet, and then you go, “Oh wait, there’s a problem.”

You have to take these extreme instances to illuminate the common faults, and that’s what the record summed up for me in a lot of ways. We’re taking these extreme versions of stories; “’49” is a surreal story set in a gold rush about a guy whose girlfriend marries someone else while he’s out prospecting. It’s sort of fanciful, but it comes back down to that same thing everyone deals with: being jilted. If you need to take a weird, fanciful story to bring that common thing back, then so be it. That’s where the idea came from, that these are all that sort of examination.

Owl and Bear: Hence the album name?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: Yeah, Common Faults. [Laughs] Because “faults” is cooler than “flaws.” I felt like “flaw” was too vowel-soundy at the end. I wanted it to resolve with a consonant. [Laughs] That’s my nerdiness coming out.

Owl and Bear: The album art was the result of a special commission from local artist Mike Maxwell. How did your relationship with him come about?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: We met Mike through Rich Cook, who has shot a bunch of photos for us. Rich has collected a bunch of Mike’s artwork and we were just introduced to his artwork. We didn’t know him at all and he didn’t know the band very much. When we first asked him if we could use one of his existing pieces for our EP cover, he had just painted that and we said we’d love to use one of his pieces.

So we’ve had this really great relationship with him because of that initial thing. He had never even intended for it to be an album cover or anything; it was just an old piece of his. This time, we wanted him to do something again. We wanted him to have more input, but we were super broke, so we told him “Hey, we can’t afford what it’s worth, certainly. We’ll still use an existing piece if you want so you don’t have to put any extra effort out there,” but he protested and was like “No, I’ll just do it in a couple of days, just let me do something.”

He really wanted to be involved, and he used some photos we took on our tour for inspiration. He ended up just painting all of us but without faces. We’ve always been really leery of photos of the band being the cover art, for whatever reason, I don’t really know why.

Owl and Bear: That’s surprising, because your press photos are so stylized.

Jeremiah Zimmerman: Yeah, they are, and we have a very specific look, but for whatever weird reason we’ve never wanted to do a band photo as an album cover or a ton of band photos in the record. I don’t know where it comes from, but Josh and I have always been really leery of that.

Owl and Bear: Do you think it takes something away from the music to show your faces?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: It might. I always feel like I would rather somebody imagine the music without the people first. I wish I wasn’t as superficial as I am, but I feel like sometimes if I see the person first, then hear the music, I make assumptions before I can catch myself. I wish I wouldn’t do that.

I don’t think we told Mike that at all, but he painted these things without anyone’s faces in it, and I thought that was the greatest thing in the word. It just appealed to me; the only way I would ever allow being on the record cover is if I’m not really there. And there were all these weird conceptual things we started reading into it once he finished the piece. It’s like the common faults thing; all that’s left on this cover are our hats and our pea coats and our style, which is all the result of vanity. It’s like: just paint the problems and take the humanity out entirely; leave the humanity for later. I don’t know what he intended — we haven’t talked about it yet — but I love the idea.

Owl and Bear: It’s funny because I often hear people’s music before I know what they look like. Then, when I do see what they look like, I’m kind of surprised. Especially with vocalists, I’m surprised that that voice belongs to that person. Like Stephin Merritt in the Magnetic Fields: that big voice coming out of that little gay man.

Jeremiah Zimmerman: Yeah, I had that same feeling with Neutral Milk Hotel. The first time I saw Jeff Mangum I was like, “There’s no way it’s that guy.” That’s what made me feel so bad about it, though. I might have written him off if I saw him walk up at a coffee shop. But I learned his music and loved it so much before I ever knew what he looked like, and I’m glad I did. In my head, I don’t want to be that shallow guy who makes assumptions based on appearances, but I do to some extent. I fight it all the time; I don’t want to do it. I think I’ve gotten better over the years, but I still do have that. And that may be why I have this reaction like, “Just don’t look at us for a while. Just listen to the thing and draw your conclusions from that, and see us later.”

Owl and Bear: The Silent Comedy began as a side project intended to involve a rotating cast of musicians. When did you abandon that idea?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: We actually had real talks about that a couple of years ago. We started talking about how, though that seems very appealing, it doesn’t really work without a central singer-songwriter. I think it works for Bright Eyes in the sense that Bright Eyes is two guys, Mike Mogis and Conor Oberst, and then they get a drummer or a bass player to back them up. It works for them, but you’re talking about a lyricist with his guitar and an instrumental genius who can play everything and owns a studio. For them, it works beautifully.

But in our situation, we don’t rely so heavily on the singer-songwriter elements of the band. I feel like Conor Oberst could go up and sing a set with an acoustic guitar and people would get something out of that and really enjoy that. And it wouldn’t be that far off from a Bright Eyes record, even if it was missing all the extra instrumentation. The essential thing is him, his voice, his lyrics, his songs.

With us, we could stay exactly like that first EP: done in a garage in Chula Vista with just acoustic guitar and vocals and a little bit of everything else. But we’ve moved toward this sort of controlled chaos, with everybody going nuts on stage; it’s become more than the sum of its parts. In the beginning, I never really accepted that I was a permanent member of the band. It seemed very much Josh’s deal, but as we kept going, Josh seemed to rely on me more and more to do the musical stuff and the arranging and the backing theory-type stuff with the music.

As it’s gone on, we’ve started to see everybody take on responsibilities and now the whole band depends on the people who are in it. It was a gradual and natural process to shift those intentions from just whoever happens to show up. The songs started to become more complex, too. And the more complex the songs are, the less you can afford to just throw anybody in. We would have shows where we would just grab anyone who was around to jump on stage: “It’s in this key, it’s these three chords, just wing it.” We would do it, and it was fine, but now we do stuff that needs more practice. The songs have some important emotional highs and lows to hit, so we need people to be there lending themselves to it.

So, to have this group of guys that were friends to begin with, I think it’s amazing that they’ve stuck with it. I’m glad that it’s them and not anyone else. Who knows how you’re going to get along with strangers for X amount of weeks. I know exactly how I’m going to not get along with these guys [laughs] so I’m totally prepared!

Owl and Bear: The album includes a poster of fans wearing Silent Comedy-inspired mustaches, which was done in part to raise money for the recording. How exactly did the fund-raising work?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: We told people, “Send us a photo—it could be Photoshopped, it could be real, it could be paper, felt, or whatever—but send us a photo of you in a mustache, and some money, and we’ll put you in the record.” [Laughs] It was basically like: we’re doing this independently, we’re self-financing everything, we don’t have anyone bankrolling this one at all, because we wanted to go to a real studio to record the drums, and we wanted to buy some equipment to record ourselves.

We knew it would be our most expensive record yet, and none of us have that money — our label is not full of money — so we thought this would be a great way for people to be involved in it. People have been so supportive. Everyone who likes the music wants to support us, and people will go so far as to hand us twenty dollars at a show for a five-dollar CD and not let us give them change.

Owl and Bear: That must be gratifying.

Jeremiah Zimmerman: Yeah, it’s an overwhelming thing for us because we’re always trying to justify the expense of things. We know that people don’t like to pay for it, with downloading music and everything; we know that. We certainly don’t expect to make millions from record sales, so we understand that no one’s just got money lying around. But [for] the amount of support people have wanted to show us, to make them more a part of it than just giving to the cause would be a lot of fun for them and for us and would be a kind of community thing.

You always hear that cliché about people we couldn’t have done it without, but in our case, it’s absolutely true. We’ve done so much work that would have gone nowhere if it hadn’t been for word of mouth, people bringing their friends to see shows, or people supporting us financially. So we thought the least we could do was put pictures of our friends in the actual record as a show of support. None of our actual faces are in there [laughs], but I don’t mind having anyone else’s in there. We got some great pictures. We got people who put mustaches on their cats, on their kids, and it was a lot of fun to get the emails with those photos.

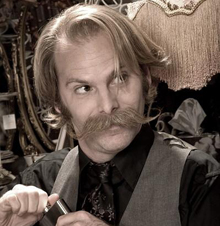

Owl and Bear: It also seems like a way for fans to pay homage to the band, since you’re such a well mustachioed group.

Jeremiah Zimmerman: Yeah the mustache thing was inspired by Justin, who has that priceless, over-two-year mustache that he’s been growing out. And we thought that, instead of just people’s faces, we might as well give them some mustache loveliness with Justin as an inspiration and put them in there.

We had that mustache party at El Dorado to kick it all off, and I think we’re going to do another record-release party at El Dorado and make it another mustache party, but this time just for fun so everyone can wear mustaches again and have the record with all the mustaches. We don’t want it to be too mustache-y; it’s super trendy and super goofy, but I think it’s fun as long as it’s not on the cover of the record, nailing ourselves to a mustache fad. [Laughs]

Owl and Bear: Have you gotten any extreme donations, on either end of the spectrum?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: Yeah, we got some that were hundreds of dollars.

Owl and Bear: Anyone just send a penny and a picture?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: No, everybody did at least ten bucks, which was really cool. And we’d get notes saying, “Hey man, glad I could support,” or “Glad I could help out,” or whatever. It’s funny to me how the money itself almost means less than the idea that somebody would give that money to help.

The attitude, the motive behind it from people, was so joyous and so celebratory, that it was really touching. I’m not a very sentimental person, but I was getting worked up over how people would gush over being able to support. I just wanted to raise some money for the record, and involve some people. I thought it would be fun, but it became really emotional. People would come up to us and give us a big hug and thank us for letting them be involved. I was like, “Don’t thank me for anything, I’m just trying to pay for the next studio session.”

Owl and Bear: Rather than putting out an album every two years, as most artists do, you’ve mentioned that you want to start a sort of ongoing subscription service for fans. What would that entail?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: We already do a thing with Modlife. They have a system where you can have a free side of your band and subscription/premium side where you pay for additional content. We don’t charge for it right now.

We like the idea of just putting stuff out continuously. We would do that in the form of videos — obviously we’d put out shirts and posters too — but videos and music. We talked about trying to do every kind of video we could, from goofing off on YouTube to tour retrospectives, interviews with fans, and every thing we can think to involve people in what we do as a band.

More and more, we’re discovering that we’re not just writing music but we also have common interests. We’re all into craft cocktails; when we’ve played at Shady Lady and El Dorado, we’ve been involved with those bars. It fits with the whole Prohibition vibe, but we all started to develop these interests that are common to everybody in the band. We’re all learning to make all these cocktails, and reading certain authors, watching certain movies, so we thought it would be fun to include people in that discussion of “here’s a lot of the stuff we like” and share that with the world.

That’s the motive behind trying to work with other artists; we’ve tried to involve certain photographers — not just one but several — and we’re always expanding that. Or filmmakers, too: we’ve worked with this girl Valerie in LA, we worked with our friend Tiffany for the “Bones” video, Kevin and Rebecca Joelson are doing some videos for us, we had Jonathan Huffman cut together the acoustic “’49” video that we did.

Our goal is to mutually benefit one another. There are already people who like our music, and there are already people who like these artists’ work. We also have this common ground of producing our creative output. There’s a growing segment of people who want to make things and put them into the world, and there’s an overwhelming number of people who only want to consume. If we can get people to start seeing things from that angle — that you don’t have to be a filmmaker to make something yourself — we can involve more people in that process.

Instead of “Okay, we made a record, buy it,” we’d do an ongoing thing. Here’s some footage of us recording the song, here’s the song, here’s the video we cut to the song, here’s the making of the video we made that we cut to the song, here’s this, here’s that, here’s this other thing. We can inspire more people to do songs or videos.

Owl and Bear: So would you continue to put out traditional albums?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: I would love to see it take the form of releasing stuff to iTunes or our own website, just every couple months we have a new little batch of songs. Then we put out a huge, multi-vinyl record set with a whole booklet in there, with some DVDs maybe, some other stuff. Similar to what the White Stripes did: I think they just did something like that, where they had the DVD, but then they had all this other stuff with it, and it was almost archival. I don’t want to do it just for the sake of doing it, I don’t want to just put postcards in there, or buttons, but I’d rather just have a whole bunch of material.

We also talked about having members of the band do companion works along with the songs. A couple members can write really well — they could write essays or short stories that are companions to the music, or film videos, or shoot stuff, or do visual art, all that stuff together.

We basically want to put out as much stuff as we possibly can on an ongoing basis, then put it in this great archival package for people who want to drop the money on a six-record set of twelve-inch vinyls of all this stuff, and maybe include some DVDs of stuff that wasn’t available.

Instead of making the tent pole of our entire career, “Man, that record better do amazingly well, or we’re out of a job,” we’ll make the ongoing output the real mainstay. We’re not trying to base success or failure on whether we sell ten million records. We play the shows, we do the thing, and when those records come out, people can either get them or not. I would love to see it move to that model so we’re not as dependent on an event-based thing for longevity.

Owl and Bear: Do you have enough material for something like that?

Jeremiah Zimmerman: We have thirty or forty songs that are un-recorded right now. If we relied on the traditional record-making schedule, it would be five or six years before all that stuff would come out. But if we can start just doing little bits at a time and putting it out in whatever form it’s in, people will get that bulk of material in maybe half the time or a third of the time. And for people that love us, that’s great for them. And for us, that’s great, because all I want to do is put the stuff out. And for people who don’t care, they’re not going to care anyway [laughs], so I don’t see what the big deal is.